It is surprisingly hard to measure how long medical research takes. A recently published study by OHE, Brunel and RAND Europe shows a better way to…

It is surprisingly hard to measure how long medical research takes. A recently published study by OHE, Brunel and RAND Europe shows a better way to do that.

In our blog post on 3rd February 2015 we described recent research aimed at analysing how long medical research takes from the first pound being spent to benefits being felt by patients or the general public as a result of that research.

Everyone would like to shorten that time span. But the information we have about just how long medical research does take to bear fruit is surprisingly hard to use to inform research policy and practice. Different studies measure elapsed times between different points in the research history of an innovation. They also measure elapsed times for a wide variety of very different kinds of innovations with rather different pathways between initial inspiration and eventual delivery of benefits: medicines, public health interventions, better ways to organise health services, and numerous other kinds of health care technology improvement.

We identified a need for a more consistent frame of reference for measuring time lags in medical research. Trochim and colleagues in 2011 described a “process marker model” which potentially contained a very large number of such process markers*. Data on most of those markers in the research history would either be unavailable for many technologies or infeasibly costly to track down. Furthermore, the complex and frequently non-linear nature of progression of research ideas through their translation (if successful) into routine use can be hard to represent that way.

As part of a recently completed research study funded by the UK Medical Research Council, OHE working with Brunel University London, RAND Europe and King’s College London, took a significant step forward in developing a method to measure time lags in biomedical and health research. See:

Hanney, S.R., Castle-Clarke, S., Grant, J., Guthrie, S., Henshall, C., Mestre-Ferrandiz, J., Pistollato, M., Pollitt, A., Sussex, J. and Wooding, S. 2015. How long does biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its translation into products, policy and practice. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(1), pp.1-18.

Having reviewed academic and policy literatures, we undertook detailed case studies of the research histories of seven very different health technologies: two medicines, a screening technology, a public health measure, behavioural therapies for two mental illnesses, and a service reorganisation aimed at early intervention.

Our approach to clearer measurement of elapsed times in research essentially comprises two main elements:

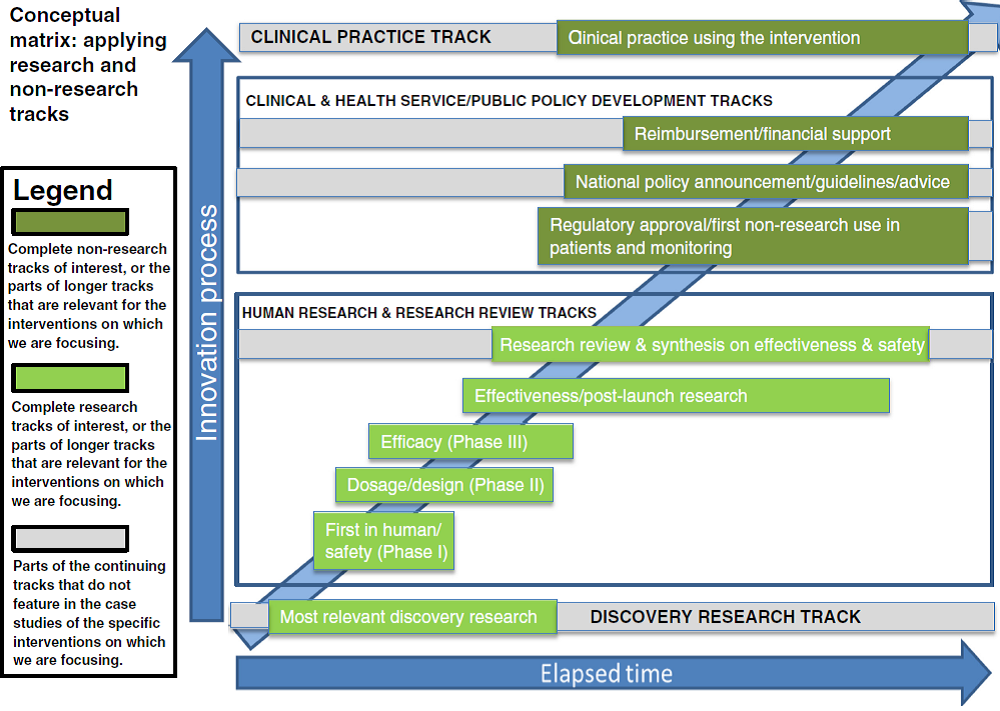

1. A matrix of the main tracks that medical research follows and how they interlink in the research history of a single health technology of any kind; and

2. A modest number of (unambiguous) calibration points between which elapsed times can be measured and compared across any kinds of medical technology.

The matrix is shown below. It consists of four main groups of tracks, two of which contain the research (discovery research and human research/research review) and two of which cover the clinical practice and public policy developments that mean the new technology gets used. The two middle groups each consist of a number of separate tracks. Some tracks (for example discovery research, research review and synthesis, policy development, and clinical practice) have an ongoing “life” of their own with activity in the track often pre-dating and continuing after the particular key events that cause work on a specific intervention to commence or cross from one track to another. This model allows analysis of elapsed times along a track and between the points at which a technology jumps from one track to another.

Source: Hanney et al., 2015.

Starting from a very long initial list obtained from the literature and our own research knowledge, we boiled that down to 11 key calibration points. These span a research history from the start date of the key research study to the inclusion of the technology in health service policy and/or formal guidance to health care providers such as clinical guidelines.

There remains much to do to analyse the length of time it takes for medical research to yield benefits, and hence to identify the areas where research could be accelerated without undue risks, and the policy changes needed to bring that acceleration about. But we have taken another step forward.

Access the full paper

here

*Trochim, W., Kane, C., Graham, M. and Pincus, H.A. 2011. Evaluating translational research: a process marker model. Clinical and Translational Science, 4(3), pp.153-162.