Transparency as a principle of good governance is not the same as transparency for improving access by lowering prices. In fact, the former often carries an…

Transparency as a principle of good governance is not the same as transparency for improving access by lowering prices. In fact, the former often carries an opportunity cost on the latter. Developing country markets are, however, dominated by generic products and encouraging competition through sharing prices makes sense if capacities are there to use the data to inform procurement decisions and protect against collusion.

Spending on pharmaceuticals and other healthcare commodities is high and makes up a large proportion of healthcare spending in rich and poorer markets alike. In this, the second of two blog posts, Kalipso Chalkidou and Adrian Towse discuss a new OHE Research Paper, published in collaboration with the Center for Global Development (CGD).

Our review of the impact of price transparency on prices and access reveals a complex picture. See yesterday’s blog post for a summary of the findings. Asking the right question seems to be as important as getting the right answer. Here we discuss five questions we think matter a lot.

Transparency as a principle of good governance is not the same as transparency for improving access by lowering prices. In fact, the former often carries an opportunity cost on the latter. See here for WHO’s latest report on fair pricing for cancer drugs, which states “…there is limited context-specific evidence that improving price transparency has led to better price and expenditure outcomes. Nonetheless, improving price transparency should be encouraged on the grounds of good governance.” Our report focuses on access and acknowledges this opportunity cost, which to us is not necessarily tradeable against stronger governance as others including WHO have claimed.

That said, the literature we draw on has a lot to tell us regarding process (as opposed to end price) transparency and its impact on access. Process transparency in government tenders, for example through the use of e-tenders, has the potential to generate significant efficiencies through reducing corruption for example, but also through improving the quality of outputs and timeliness of delivery. For example, e-procurement in India improved road quality and in Indonesia it significantly reduced project time overruns.

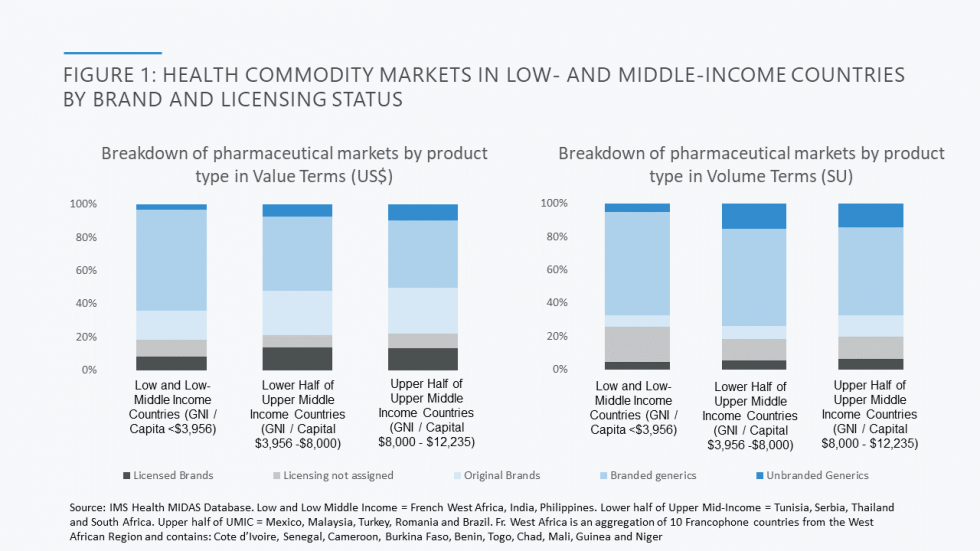

Developing country markets are dominated by generic products. As set out in the Figure below, two-thirds of the market by value in low and lower middle-income markets included in CGD’s analysis goes to, almost exclusively, branded generics. Further review of data from a subset of countries (the Philippines, India, and 10 countries in French West Africa) reveals that less than 10 per cent of the pharmaceutical market comprises on-patent products; the remainder of originator products purchased are older and off-patent, launched globally over 20 years earlier and therefore genericised long ago in most markets (look out for the forthcoming report from CGD’s Working Group on the Future of Global Health Procurement for more detailed data).

This is a very different state of affairs to high income country markets such as those in the US and UK, where generic competition generally works. In the US, for example, generics account for 90% of prescriptions dispensed but for less than a quarter of total drug costs. The UK figures are similar. In contrast, in some of the poorest SSA and South Asian markets, the volume/value relationship between generics’ volume and spend is roughly 1:1. So, when it comes to developing country markets, it is the price of generics as opposed to on patent products that, at least for now, matters the most.

The literature suggests that price transparency for on-patent products, where clinical differentiation is significant and alternatives few, will reduce access by linking markets and undermining price differentiation as between high income and low income markets. This is not surprising. In a recent piece, Kremer and Snyder find that impeding price discrimination across countries by imposing price controls or capping price at a % of the US price (policies roughly equivalent to linking markets through price transparency) increases deadweight loss for drugs and vaccines by over 50%. They also find that a monopolist manufacturer of a vaccine or drug “…does just about as well if it has to rely on the United States as its sole revenue source as it would if it served the whole world at a uniform price.”

For off-patent products, on the other hand, encouraging competition through sharing prices makes sense with the provisos the right type of price information is shared and compared, the capacities are there for using the data to inform product selection and procurement decisions and that one can protect against collusion (more on all three of these below).

Price comparisons across countries are notoriously hard to do meaningfully. Although long archived, the Office of Fair Trading (now defunct) analysis of pharmaceutical pricing in the UK offers a nice overview of the challenges of cross country price comparisons here.

Our price transparency analysis distinguishes between and makes separate recommendations for procurement level or import (so-called cost, insurance and freight – CIF) prices and prices to patient post procurement, which in LMICs become seriously inflated across the supply chain due to, amongst other things, transport costs, costs of capital and exchange rate fluctuations. We recommend that generic product prices at both the procurement and patient transaction levels are shared to encourage competition amongst suppliers and accountability of buyers/budget holders where there is pooled procurement.

Price transparency for commoditised products can lead to collusion with one-off savings followed by losses to payers as suppliers form cartels and divide up the market to protect their revenues or tacitly collude using disclosed prices as signals to reduce competition. There are several examples of such colluding behaviour from the literature, so we recommend that any generic product pricing databases ought not to be shared with suppliers.

Instead, we propose a buyer-only centralised database of ex-factory off-patent product prices at a ‘pack’ level including strength, formulation, volume (SU) and pack size, but anonymised to be made available to country and development partner buyers. Such a database would enable further analyses including benchmarking given volume, value and disease burden breakdown across markets and geographies. That said, price information must be used responsibly as, buyers using knowledge of prices across markets to drive them down may well result in substandard products or market exit es

pecially from remote rural areas, as has been observed in Indonesia and also in India.

A model worth considering is that of ECRI, a membership-based model whereby providers (and payers) can join and share the prices they get for medical devices and capital equipment in return for accessing performance, pricing (and safety reporting) databases for a wide range of products across geographies (now increasingly beyond the USA) as well as evidence-based contextualised cost effectiveness briefs is a model to be considered, especially in the world of medical devices and equipment oftentimes excluded from price benchmarking and evidence conversations. Not dissimilar to the ECRI model, NHS England set up a database for sharing information amongst providers including a league table for all NHS hospitals and the Model Hospital website which includes commodities as well as services and infrastructure. In an attempt further to reduce price variation, the NHS has also developed benchmarking works based on e-procurement prices to derive a comparable price index providers (not suppliers!) can use to see how well they are doing price-wise compared to their peers.

Will the price information be used (or, why are buyers not using existing databases available to them now?)

Currently, no centralised, up-to-date, accurate, exhaustive and user-friendly price database exists. Instead, pricing data tend to be proprietary and owned by major players such as IQVIA (though smaller players such as mPharma in SSA are starting to change this) who collect and clean up the information making available at discounted costs for researchers and commercial rates to pharma companies. That said, there are several sources of information currently available and which a national insurance agency or procurement authority could use to benchmark itself against others and use as a lever for negotiating a better price with suppliers if it so wished.

For example, working with the Ghanaian National Drugs Programme, one of us identified the potential for efficiencies for specific generic antihypertensive products for which the Ghanaian National Health Insurance Scheme was getting a worse deal than the British National Health Service. This was done using the British National Formulary, available to all those with a UK IP address. The NHS Drugs Tariff is also available online (listing reimbursement prices to pharmacies rather than the acquisition price paid by pharmacies) and, for hospitals, the eMIT national database. The WHO list a whole array of pricing databases, some disease (e.g. HIV) or product (e.g. vaccines) specific, some region specific and some giving patient level prices (e.g. HAI). Then there is the World Bank’s International Comparison Programme. The European Commission has invested in sharing prices within its borders (e.g. see Euripid) and other regions including the LAC with PAHO support are likely to follow suit (e.g. RedETSA’s price database is work in progress).

However, these data are not sourced, cleaned and used to achieve procurement efficiencies. And even if, as we saw in the ECRI and NHS examples earlier, it takes quite a bit of effort to do all of the above, it is surprising that LMIC national procurement agencies, spending large amounts on buying commodities, or the development partners that support them including large funding conduits such as the GFATM, have not embarked in a systematic effort to address inefficiencies in the commodities market through the careful application of price transparency. The GFATM does have the PQR database which is however incomplete and out-of-date and in any case only includes TB, HIV and malaria commodities. The CGD’s Working Group on the Future of Global Health Procurement found that the total market size for healthcare commodities in 43 SSA and South Asian LICs and Lower MICs is almost $50bn with less than 10% of this spent by donors, which makes rather pressing the need to include non-MDG commodities, including generic products for chronic conditions, in any pricing database.

All in all, price transparency is hard to define, and pricing data are hard (though not impossible) to find, clean up and present in a useable fashion. In many cases, referencing processes and institutions may be a safer bet than copying each other’s prices. As one of us has previously discussed, the biggest question of all remains: can we pool our resources to buy better together?

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the authors and do not represent those of any institution.

Berdud, M., Chalkidou, K., Dean, E., Ferraro, J., Garrison, L., Nemzoff, C., Towse, A. (2019). The Future of Global Health Procurement: Issues around Pricing Transparency. Research Paper 19/04, Office of Health Economics. RePEc.