Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

The first 10 drugs included in the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program created by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) were announced at the end of August. We discuss what they are, what they show us, and the potential ripple effects.

While there are various provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act, the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program has drawn the most attention, being the first time that the US government has the authority to set drug prices. Although labelled a “negotiation” program, it is unclear how much leverage manufacturers will have, with high penalties imposed on companies refusing to participate or not accepting the Maximum Fair Price (MFP) that is set by the process.

As we explain in our free online Educational Program on the IRA, the drugs that qualify for selection include single-source drugs or biologics with the highest total Medicare Part B & D expenditures, approved by the FDA 7 or more (for small molecules) or 11 or more (for biologics) years ago. Any form of the qualifying drug with the same active ingredient is swept into the process—which means a drug approved by the FDA only last year could be subject to price setting if it uses the same active ingredient of an older qualifying drug.

Which drugs are on the list?

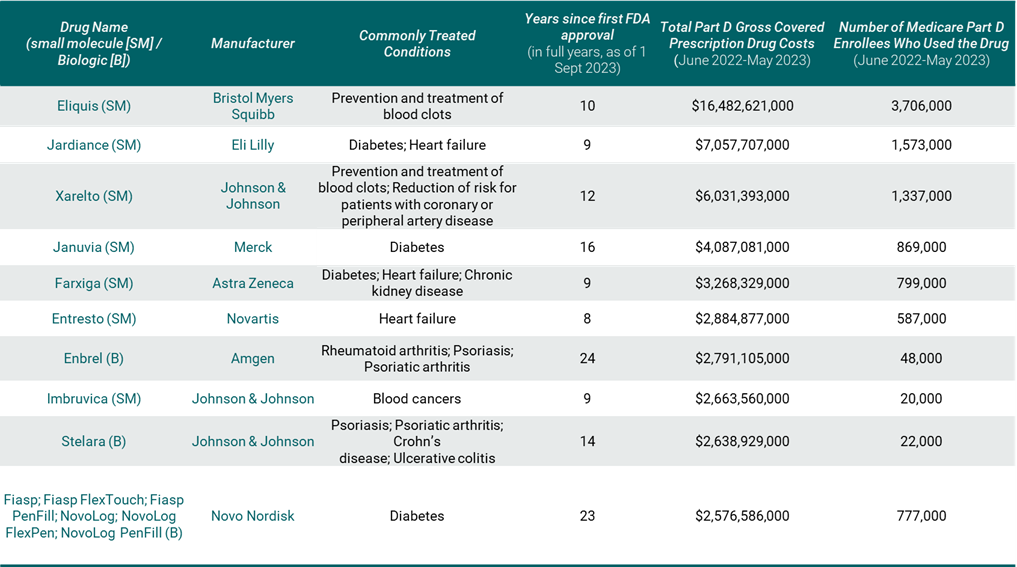

On August 29th, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first 10 drugs selected for price negotiation. Their key characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. The 10 pharmaceuticals selected by CMS for price negotiation

Source: CMS (2023), supplemented by FDA approval data

The 10 selected drugs include seven small molecules and three biologics that are broadly used in the Medicare population, produced by eight manufacturers. Around 8.25 million Medicare Part D enrollees used at least one of the drugs over the last year, according to CMS (2023); this equates to around 17% of the enrolled population. The list includes drugs that primarily treat chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, blood clots and chronic kidney disease, and more than half of the drugs treat more than one condition. Two of the drugs are used to treat autoimmune disorders such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease. There is only one oncology drug on the list.

The products on the list account for just over $50 billion in Part D gross covered prescription drug spend over the last year. However, gross spend does not account for rebates and discounts that are applied in practice and net spend is likely to be much lower for many products on this list, given the significant brand competition in several therapy areas. In fact, six of the 10 drugs on the list are in therapy classes where average rebate levels exceed 40% (MedPAC, 2023). According to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), diabetic therapies account for the highest levels of negotiated manufacturer rebates, at over 50% of gross spend (MedPAC, 2023, p.160, chart 10-21). It is therefore possible that some of the drugs that didn’t make the list are actually costing Medicare more than the ones that have been included in this first round of negotiation.

Half of the 10 selected drugs have generic or biosimilar competitors on the horizon; it is for this reason that some highly sighted predictor lists left several of the selected drugs off their forecasts (Dickson & Hernandez, 2023; Wingrove, 2023).

What now for those on the list, and will the Inflation Reduction Act’s policy objectives be met?

Manufacturers of selected drugs had one month – over September 2023 – to submit data to CMS for consideration. To the extent that CMS considers a drug’s clinical benefit in determining its price, real-world effectiveness data could have a critical role to play in price negotiations over the coming months, given the drugs on the list have already been used by Medicare patients for several years (13 years on average). By February 1st 2024, CMS will make their initial price offer, which kicks off a deliberation process that concludes on July 31st next year. The final MFP will be published on September 1st 2024, taking effect on January 1st 2026.

Through the introduction of the IRA’s Drug Price Negotiation Program, the US government set out to address a perceived market failure: insufficient timely competition to bring down high drug prices. The characteristics of these first 10 medicines suggest the program may not be targeting, at least initially, medicines for which the market isn’t already working to some extent to control costs. This list is characterised by drugs with high gross spend due to high volume (they treat highly prevalent diseases), high levels of rebates due to competition within their therapeutic classes, and pending generic or biosimilar competition. Therefore, the extent to which the program is effectively targeting those medicines for which the market is failing to lower costs is a new question for economists to debate.

The IRA was signed into law one year ago. The publication of this list marked the start of a one-year period of information gathering, deliberations, and likely contentious discussions about what constitutes a “fair” price. The true impact on prices and Federal drug spending has yet to be seen. But what of the broader and longer-term implications of the IRA and how has the economist community reacted to this monumental reform in drug policy?

IRA impact? Insight from three international conferences

The Inflation Reduction Act was top of the agenda at key international conferences over the Spring and Summer this year. At the ISPOR International Annual conference, held May 8th – 10th in Boston, health policy stakeholders came together to discuss the IRA and speculate on the potential impacts (see this blog for key themes arising). DIA’s 2023 Global Annual Meeting took place the following month, offering an important platform for life sciences professionals and stakeholders to discuss the IRA and what it means for that group. Just a couple of weeks later, IHEA – a bi-annual meeting of a global community of health economists – took place in Cape Town, offering a global perspective on this US policy.

Reflecting on our observations, contributions, and discussions – formal and informal – at these three very different conferences, we can summarise three major themes:

1.The process CMS will follow in setting prices is unclear

Top of the agenda at conferences like ISPOR were questions around methods: how will the MFP be determined, and therefore, where will the price end up and why? The downward direction of prices is a given, but it matters how you get there. CMS has shared the list of considerations, which include clinical benefit and manufacturer-specific data. But how these data will be quantified, combined, and weighted is a current unknown. We may get some window into CMS’ decision making by March 1st, 2025, when CMS publishes the MFP explanation for the first 10 drugs, but the level of detail CMS is expected to publish is also unclear. While there is significant speculation about CMS embarking on health technology assessment (HTA), whereby price is evaluated as a function of measured clinical benefit, it is difficult to conceive how this HTA construct fits within a process that must also factor in aspects like research and development (R&D) cost recoupment and remaining patent life. Lack of clarity in CMS’ guidance on its process and methods affect predictability, and – if these remain opaque – could challenge public trust and confidence in the process.

2. IRA alters incentives for innovation

At ISPOR and DIA, investors were keen to highlight the projected hit on operating income for the biopharma industry and the cuts to R&D that would ultimately follow. Whatever people’s thoughts on the aggregate level of impact on innovation, what seems certain is that some technology types or disease areas will be impacted more than others, based on how the IRA is designed and which drugs are eligible for price setting.

Investment in biologics may be favoured over small molecules given the longer lead-in before price setting, and as a result, diseases that are best treated by small molecules – like cancer and neurological disease – may be impacted most. In addition, certain disease areas that primarily affect the older Medicare population – such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and neurological conditions – will be disproportionately impacted.

Given the timing of eligibility for price setting – 7 or 11 years after the launch of the first indication – much discussion about the IRA’s impact focused on the resulting de-prioritisation of post-launch research. For many drugs, new indications are investigated and identified after initial FDA approval. This is particularly true of oncology drugs, but multi-indication medicines are common across therapy areas. If manufacturers expect a price cut to be imminent, they are less likely to invest in R&D to bring a new indication to market. Likewise, they may be more likely to delay launching a new medicine indicated for a smaller patient population (including orphan or rare diseases) until data can be collected for approval for a larger indication, given that initial approval begins the clock toward price setting.

Already, in response to CMS announcing the first 10 drugs subject to price setting, manufacturers of Entresto have indicated that they may not have invested in further trials for extended uses of the drug for heart failure, including for paediatric populations, had the IRA been implemented when they made those decisions (Taylor, 2023). At ISPOR, pharmaceutical company representatives reiterated this point, which was also highlighted from a rare disease patient perspective at DIA. For rare diseases, the use of existing licensed medicines in new rare disease indications represents a significant and efficient source of new treatment opportunities, which could be disincentivised by the IRA.

3. Implications for industry revenue and global R&D may be larger than initially projected

The US pharmaceutical market is the largest in the world. Coupled with high healthcare expenditures, the US also enjoys the broadest and fastest access to medicines globally. Among the biggest questions that polarize opinion on the IRA are: how significant will the IRA be in cutting expenditure for the US government and profitability for industry and, critically, what will that mean for pharmaceutical US R&D leadership and to innovation and patient access to medicines in the US and globally?

While the primary aim of the IRA is to reduce spending for Medicare – its impact will be broader. Within the US, there will be spillovers to other US markets via the Best Price for the Medicaid Rebate Program, the 340B ceiling price, and the calculation of Average Sales Price (typically used as a pricing benchmark in the commercial market). It is also likely to affect competitive dynamics in Medicare Part D more broadly, with competing products in impacted therapeutic classes facing pressure to match the government-set price, further reducing industry revenue. Whether price pressures will impact the standing of the US as a first-launch market in the longer term depends on how implementation or any evolution of the IRA plays out.

What about global spillovers? The IHEA conference offered an opportunity to reflect on whether reimbursement in the US market – given its size and importance for global pharmaceutical companies – will impact global drug pipelines and thereby influence access across the rest of the world. We heard from attendees there that whatever happens in the US tends to have ripple effects globally. The potential benefits arising from price reductions – and whether those benefits reach patients – should be carefully studied and compared with the widely aired concerns around R&D impact.

The opinions expressed are those of the author alone. Dr Cole received no funding for this article, but has undertaken related work on the topic of the IRA with funding from PhRMA.

References

CMS, 2023. Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program: Selected Drugs for Initial Price Applicability Year 2026. [online] Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/fact-sheet-medicare-selected-drug-negotiation-list-ipay-2026.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug. 2023].

Dickson, S. and Hernandez, I., 2023. Drugs likely subject to Medicare negotiation, 2026-2028. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 29(3), pp.229–235. 10.18553/jmcp.2023.29.3.229.

MedPAC, 2023. Data book [online] July 2023. Available at: https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/July2023_ [Accessed 30 September 2023]

Taylor, P., 2023. Novartis hits back at Entresto selection on Medicare list. [online] pharmaphorum. Available at: https://pharmaphorum.com/news/novartis-hits-back-entresto-selection-medicare-list [Accessed 5 Sep. 2023].

Wingrove, P., 2023. Drugmakers brace for list of first 10 drugs for US price negotiations. Reuters. [online] 2 Aug. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/drugmakers-brace-list-first-10-drugs-us-price-negotiations-2023-08-02/ [Accessed 30 Aug. 2023].

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!