Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Since we began our project to consult experts on the impact of H.R. 3. on pharmaceutical innovation the CBO has released a new working paper. Given our research has led us to conclude that the CBO’s initial policy evaluation was…

Since we began our project to consult experts on the impact of H.R. 3. on pharmaceutical innovation the CBO has released a new working paper. Given our research has led us to conclude that the CBO’s initial policy evaluation was an unreliable predictor of the impact of H.R. 3 on innovation and shouldn’t be used to guide policymaking, it is important to ask whether the latest paper changes this.

The main conclusions from our evaluation of the new CBO report are:

1. The new report doesn’t model exactly the policy proposed under H.R.3. and is therefore irrelevant to the current policy discussion.

2. The model is also fails to adequately represent the reality of biopharmaceutical investing and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon to guide policymaking.

3. Many of the criticisms of the original analysis remain making the results unreliable.

The latest CBO report does not change our earlier analysis and in particular our main conclusion that H.R.3. will not curb overall cost growth or make healthcare more affordable or accessible for the average American. Broader reform of the US healthcare system is required to address these fundamental issues.

Previous CBO work in this area has used three industry average figures to estimate the impact of H.R.3: the estimated average impact of H.R. 3. on revenues, the estimated relationship between revenue and the number of new drugs developed (the elasticity of innovation), and a baseline estimate of the future annual number of new drugs in the absence of any policy change. All are subject to uncertainty and indeed all have been contested as described in this series.

The new CBO working paper focuses on one of these criticisms – the elasticity of innovation. Instead of the CBO selecting its own elasticity (0.53) informed by the historic literature and applying this at an industry level, the primary purpose of the new paper is to build a model from the individual product level linking the expected net returns and R&D decision-making throughout the clinical trial programme.

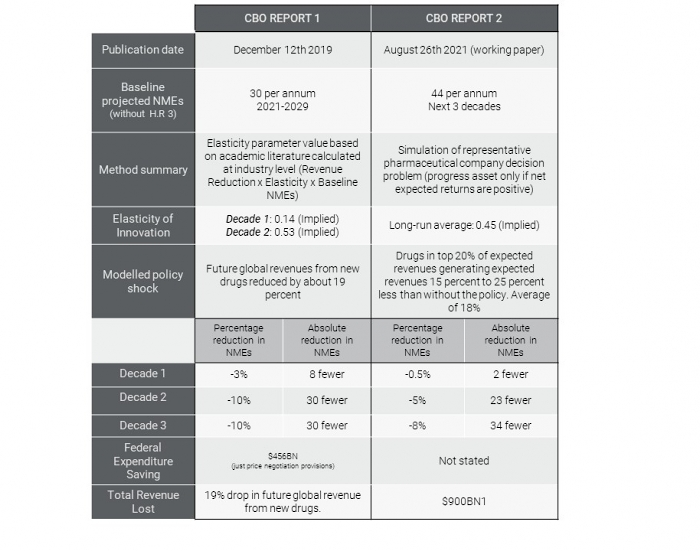

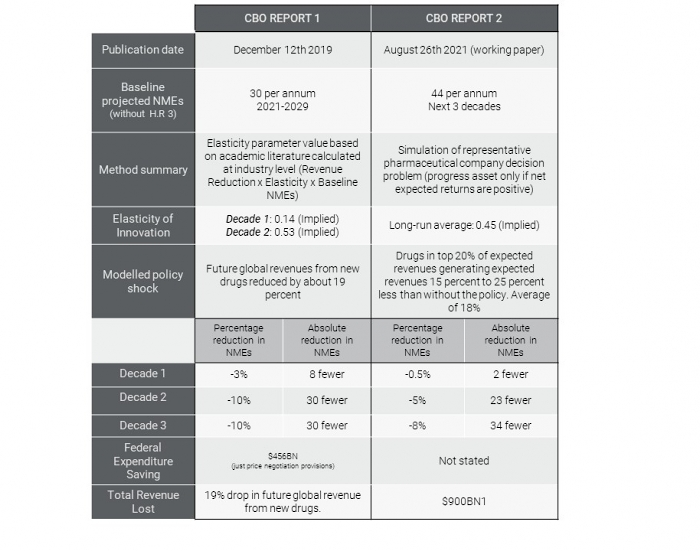

The working paper does not explicitly evaluate the impact of H.R. 3, but rather “a representative policy that affects expected returns similarly to the one proposed in H.R. 3.” However, it is not clear that the policy evaluated in this latest CBO study is equivalent to H.R. 3. As the table below illustrates, the CBO in their earlier work had estimated that H.R. 3 would reduce global pharmaceutical revenues by 19%. This latest work evaluates the impact of a policy that would reduce the revenue of the “blockbuster” drugs – those in the top quintile of Medicare expenditure – on a sliding scale of 25% to 15% with an average effect of 18%. This is hard to reconcile with the estimated average Medicare price reduction of 68% in Table 2 of the CBO’s original analysis.

Comparison of the methods and findings of the two CBO analyses.

Sources: CBO report 1: H.R. 3, Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act CBO report 2: CBO’s Simulation Model of New Drug Development: Working Paper 2021-09

The other major change is that the CBO have increased their estimate of the baseline level of innovation – the number of new drugs we would expect to see each year without any change in policy – by approximately 50% (from 30 to 44). This, ceteris paribus, would increase their estimate of the impact of the policy in their original evaluation by 50% but there have been no updates or revisions to that original work.

What doesn’t change in this new report is the significant uncertainty in the level of impact on innovation. Nor does the new report provide any insight into the cost of the policy in terms of health. For example, Buxbaum et al find that 35% of the increase in life expectancy of 3.3 years in the period 1990-2015 is due to drugs. We do not know what innovation we will lose and what the ultimate impact on the length and quality of life will be.

Whilst this latest approach is significantly more sophisticated than their original method of using average industry effects, to make a model of product level investment decision-making tractable, the CBO have made numerous simplifying assumptions. Precisely because these assumptions don’t adequately represent reality, the CBO’s model will lead to erroneous conclusions whether it’s used to evaluate the impact of H.R.3 or any other policy.

One simplification the CBO make is that all product decisions are independent. Yet this does not reflect the reality that the returns across the portfolio of pipeline investments are what influences decision-making in the de facto “blockbuster” model of patented product innovation that we observe in biopharmaceuticals.

A large portion of total revenues from new drugs are concentrated among the top-selling drugs. A review of expected revenues from 2020 FDA approvals found that the share of top decile was 59% of the total. The CBO’s own analysis (Figure 2) leads it to note that “lifetime revenue for Medicare Part D drugs is heavily skewed.” Research has found that only a third of new drugs return a profit, and many never make it to market at all. Investors know this and need to know that high value products will get high returns. The skewed returns from R&D have been likened to those from venture capital or IPO investments.

The CBO also assume that the level of return is irrelevant: as long as there is a positive return (i.e. expected revenue > expected costs) products will continue to be developed. Their measure of the impact of the policy on innovation are the number of drugs which now fall below the expected breakeven level after the policy is introduced. As our recent study illustrates, the CBO model does not reflect the reality of how investment decisions are made. Whilst the decision rules of individual investors are different, they all have a threshold of expected returns which is a multiple of their investment (the cost of development) and a maximum period in which they expect to recover their capital.

Another simplification is that, like the original evaluation of H.R. 3., this new model takes preclinical investments as exogenous or given, implying that policies like H.R. 3 would have no impact on the pool of potential assets for phase I investment. This is unrealistic, and as result, the CBO model will underestimate the true impact of price-setting policies on total innovation. Much of the translational end of preclinical work is done by emerging biotech companies who need venture capital. If the value of successful innovation decreases due to lower expected revenues, this will filter down through the innovation supply chain—with less preclinical development reducing the available pool of assets. The “valley of death” is a well-established phenomenon in pharmaceutical R&D and policies such as H.R.3. are likely to exacerbate this further. As one investor told us: “What you’re going to see early on is healthcare venture investors will freak out. There will be a fairly long period of time in which there will be highly restricted fund flows, and it will have a devastating impact on the industry.”

The latest work from the CBO is interesting and the level of effort invested demonstrates the importance of the debate. However, the new study does not shed any light on the H.R. 3. debate for two critical reasons: (i) it doesn’t model exactly the policy proposed under H.R. 3. but instead evaluates a policy with a similar average effect yet very different distributional effects, and (ii) the model is theoretically flawed and fails to adequately represent the reality of biopharmaceutical investing. An overly simplified model that does not approximate reality may have some academic interest, but it cannot be reliably used to inform policymaking.

Many of the criticisms of the original analysis remain. The relationship between revenue and innovation (the so-called elasticity of innovation) is implausibly low. There is no accounting for heterogeneity in the impact across therapeutic areas, no account for how science and therefore the cost and risk of R&D has changed, and no measure of the impact on the health of the population.

From the start of this project, one thing was clear from the experts we consulted: H.R.3 was the wrong policy for the wrong problem. As proposed, H.R.3. is intended to save the government money. It will not curb overall cost growth or make healthcare or even drugs more affordable for the average American, nor will it lower out-of-pocket expenses, or increase access to healthcare. Broader reform of the US healthcare system is required to address these fundamental issues.

Endnote:

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!