Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Our second blog in the OHE H.R. 3 Series discusses how the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)’s analysis of H.R.3 does not reflect the reality of biopharmaceutical investing. Our second blog in the OHE H.R. 3 Series discusses how the Congressional…

Our second blog in the OHE H.R. 3 Series discusses how the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)’s analysis of H.R.3 does not reflect the reality of biopharmaceutical investing.

Our second blog in the OHE H.R. 3 Series discusses how the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)’s analysis of H.R. 3 does not reflect the reality of biopharmaceutical investing.

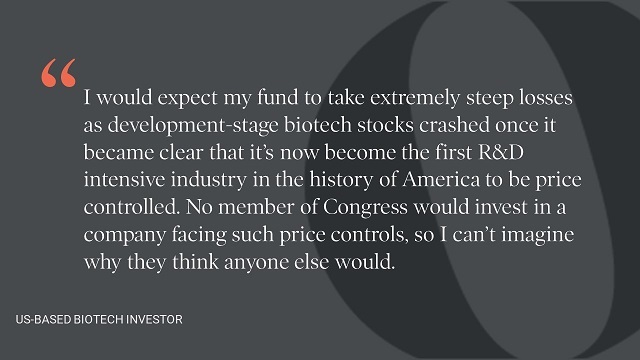

Drawing on insights from interviews with 11 major investors from the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, venture capital, and private equity communities, we conclude that the CBO’s estimates are likely to significantly underestimate the impact of H.R. 3 on innovation. We share 5 lessons we learned from our investor interviews which highlight that the process of investing is much more nuanced than in the CBO model.

The CBO has released three estimates of the potential impact of H.R. 3 and H.R. 3-style price caps on investment in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D). CBO’s initial two analyses do not explicitly model the investment decision problems facing the individual pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. They simply assume a value for the elasticity of drug innovation (i.e., the relationship between a reduction in revenue and outputs of innovation) to expected revenues based on estimates from the academic literature at an aggregate industry level. Our later blogs will unpack why these model parameters are problematic.

In a recently released white paper, the CBO attempts to explicitly model the decision problem facing the individual drug developer in a dynamic model with uncertainty. The model aims to reflect the behavior of a generalized investor choosing to progress a drug candidate into the next stage of clinical development if expected returns exceed expected costs. This is an overly simplified decision rule that does not accord with our findings from our investor interviews.

Our interviews suggest that the CBO’s generalized model is unlikely to reflect the reality of investment decision-making.

Many of the investors interviewed stated that investment decisions boil down to the probability that the project results in an approved product and the value of the product if it is approved. Therefore investment decisions are made by balancing the probability of technical success and the probability of commercial success. While H.R. 3 impacts the probability of commercial success, because decisions are made based on these two probabilities together, investment in areas with high risk may also be affected.

It is natural to think that the main object of interest for drug developers is the individual drug. It is also easier to model this type of behavior as the CBO do in their most recent analysis, which we cover in more detail later in this Series. However, this is not necessarily how investors make decisions in practice. Although identifying the basic risk-return profile of a given asset is an important ingredient in investment decisions, it is ultimately the returns across the portfolio that are important. In an R&D portfolio, the winners pay for the losers and significantly reducing the returns for the winners would have an adverse impact on the entire development portfolio — another unintended consequence of H.R. 3.

Those we interviewed as part of our study brought our attention to a clear dividing line in how decisions are made. For early-stage decisions (i.e., well before phase III trials that are used to demonstrate that a drug is safe and effective), unmet need and the company’s historical areas of success were cited as important factors in investment decision making. However, on the precipice of phase III trials, sophisticated financial and/or commercial analysis is typically required to estimate the risk-adjusted return that we mentioned earlier. Any quantitative thresholds or cut-offs in willingness to invest were also a function of risk and conditional return.

Our interviewees clearly believed that H.R. 3 would significantly reduce the reward side of their calculations rather than significantly altering the risk landscape, as the policy is currently written. As a result, biopharmaceutical companies would have less capital to allocate to R&D in general, but particularly for the higher-risk disease areas, such as neurology, where the underlying science is less well understood or where the regulators might be concerned about the safety of the drug.

Our interviewees painted a nuanced and complicated picture of the likely impact of H.R. 3. In the short term, from an investment standpoint, mid-size and big pharma would try to cope with expected revenue cuts by maintaining programs that had reached phase 2 or phase 3 through cuts to operating budgets. The response by venture capital and private equity, however, would be more immediate and pronounced. Those we interviewed predicted significant cuts to early-stage development activities resulting in a substantial decrease in the number of novel molecular entities over time. Early-stage capital is highly mobile and will seek the highest risk-adjusted returns, which would likely be in another sector outside of biopharmaceuticals.

Our interviews with investors suggest that a high-level policy evaluation such as the CBO analysis is likely to underestimate the potential risks to biopharmaceutical R&D, risks that would ultimately have adverse consequences for population health—both in the US and globally. In the face of rapid scientific progress, such as we have seen with the development of COVID-19 vaccines and cell and gene therapies, using historical average relationships along with conservative projections of biopharmaceutical R&D outputs is not a sound basis for an unprecedented policy change. This is especially true in the case of H.R. 3, which targets products with the highest expected returns.

All models are wrong, but some are useful (so the saying goes). The CBO’s model will surely be wrong and most likely not useful for projecting the impacts of H.R. 3.

The next blog in the Series will focus on an important area of criticism of the CBO evidence, related to their measure of pharmaceutical innovation and what it fails to tell us about the impact of H.R. 3.

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!