Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

Medicines are responsible for a substantial proportion of these emissions, at an estimated 25% of health service emissions in England. Anaesthetic gases and inhalers are often highlighted as particularly problematic; in England they contribute two and three percentage points of total NHS GHG emissions respectively.

Among the different types of inhaler, pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) are responsible for the greatest emissions, indicating the greatest scope for change. Indeed, carbon minimal pMDIs are in development, expected to reduce carbon emissions by around 90% compared to existing pMDIs, with no expected change in clinical outcomes or additional cost to the health service.

The primary purpose of this report is to establish the additional economic value of carbon minimal pMDIs compared to existing pMDIs with the same active ingredient. A secondary aim is to explore the feasibility of assessing the value of environmental impacts (in this case GHG emissions) in an economic evaluation, comparing different approaches for doing so. To meet these aims, a series of literature reviews were undertaken, followed by calculations of the economic value of the new carbon minimal pMDIs via simple economic modelling.

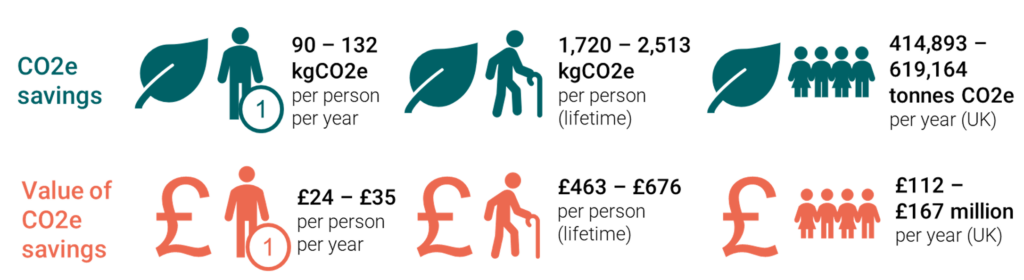

Summary of key results: Carbon footprint and carbon values for standard and carbon minimal pmdi

Notes: results ‘per person’ comprise all people with asthma in the UK, results ‘per year’ comprise all people using pMDIs (not limited to asthma).

In relation to our secondary aim of exploring the feasibility of including GHG emissions data in economic evaluations, we find that the additional value associated with lower emissions can be calculated as part of health economic evaluation, where data availability allows. This is typically achieved via two main alternative approaches: 1) integrated evaluation: whereby the carbon savings are converted into health or financial effects and incorporated into the usual incremental cost effectiveness ratio, or 2) parallel evaluation, whereby additional metrics (incremental carbon footprint effectiveness ratio [ICFER] or incremental carbon footprint cost ratio [ICFCR]) are calculated and presented alongside the usual ICER. We suggest that a metric reflecting the cost per kgCO2e saved (which reflects an incremental cost carbon footprint ratio, or ICCFR) has a more intuitive interpretation for decision makers than the ICFER or ICFCR.

In this case the carbon minimal pMDI dominates the existing pMDI (note this assumes the same active ingredient in both versions of the pMDI), as it is the same or superior across all categories of outcomes (health, financial and GHG emissions). The decision between the two technologies is therefore uncomplicated. However, the decision between two options will be less clear when an intervention does not dominate its comparator. Further research into how environmental data and related metrics can be used to inform healthcare decision making as part of an HTA process, for example via the development of decision rules, in such circumstances is required. Additional research into how the use of environmental data in economic evaluation and HTA can work alongside other incentives for the wider health system and related stakeholders to reach their net zero goals is also critical.

Establishing the Economic Value of Carbon-Minimal Inhalers