Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

How does NICE’s severity modifier work?

NICE implemented a new severity modifier in February 2022 as part of a wider update to its methods. Its aim was to broaden the definition of severity beyond the existing end-of-life severity modifier to also consider improvements in quality of life.

The revised approach considers two different – but related – measures of disease severity: absolute shortfall (AS) and proportional shortfall (PS). Greater value is assigned to health gains for patients with greater absolute (AS) or proportional (PS) health shortfalls, based on whichever shortfall is greater.

Under NICE’s current criteria, patients who lose a substantial amount of their future health can qualify for a value ‘multiplier’ of either 1.2 or 1.7. NICE applies this multiplier to health gains when calculating the cost-effectiveness of a treatment. This has the effect of increasing the quantity of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) gained with treatment and decreasing the effective cost per QALY gained, making a recommendation by NICE more likely relative to treatments for conditions that do not qualify for the modifier.

Patients expected to lose between 85% and 95% of their (discounted) expected lifetime quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or between 12 and 18 (discounted) QALYs relative to an individual without the disease receive a multiplier of 1.2.

Patients who are expected to lose more than 95% of their (discounted) expected lifetime QALYs or more than 18 (discounted) QALYs relative to an individual without the disease receive a multiplier of 1.7.

Gaining a better understanding of UK societal preferences

We conducted a quantitative preference study to understand how well the criteria of NICE’s severity modifier align with UK societal preferences. Our primary objectives were to estimate:

We used a Person Trade-Off (PTO) approach to understand the value of health gains to patients with a greater versus lesser future health in an age-sex representative sample of the England & Wales general population (complete case analysis N=990). We also elicited their views on severity thresholds and key principles of resource allocation.

What our research tells us about the UK values health gains and losses

We found that members of the general population give priority at a substantially lower shortfall thresholds, and that the public assigns greater relative value to health gains to more severe conditions at almost every level of severity, compared with NICE’s current severity modifier.

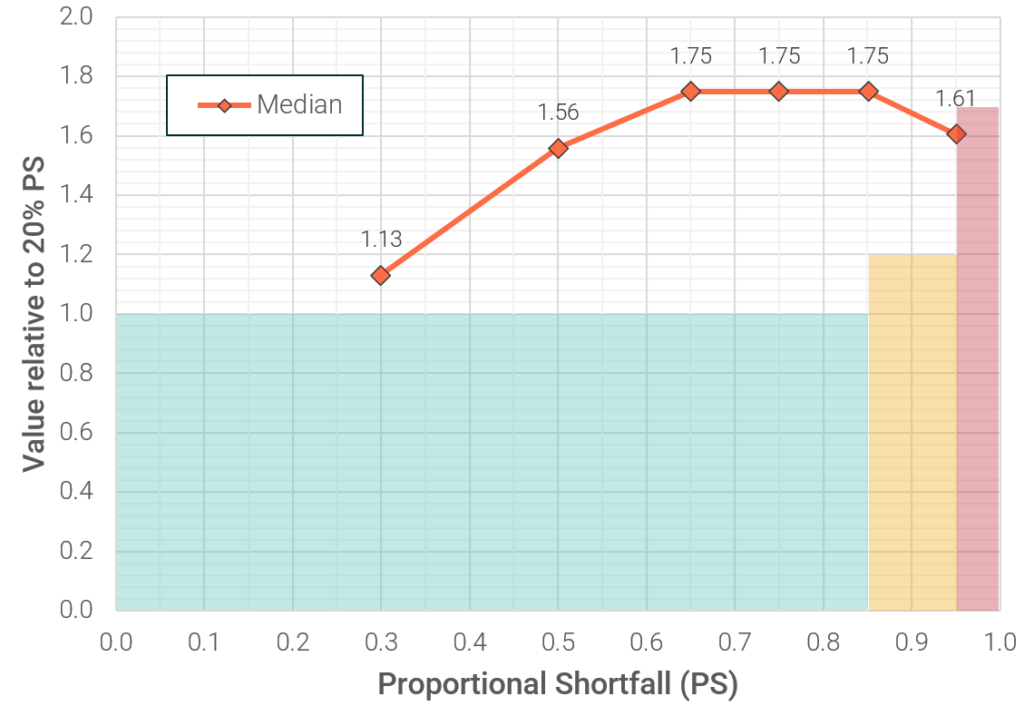

We identified the shortfall ‘cutoffs’ for what respondents considered “severe” or “very severe”. On the proportional shortfall (PS) scale, the public indicated that ‘severe’ health states started around 50% PS (compared to NICE’s 85%) and that ‘very severe’ health states begin around 65% (compared to NICE’s 95%).

We also found a fairly rapid increase in the relative value of treating more severe patient groups, even at relatively moderate levels of shortfall, and that relative value plateaus at about 1.7 beyond a PS of 65%. This plateau in value around 65% PS is consistent with the cutoff identified in a separate task and reinforces the notion of critical threshold in public preferences at this shortfall.

* Excludes mean weights. See Figure 11 in the main text for mean and median weights.

Policy implications and next steps

Our results suggest that NICE’s current severity modifier is not well aligned with the UK public’s preference for prioritising health gains for more severe diseases. If NICE seeks to align the value and priority assigned to new medicines and technologies with societal preferences, these results suggest a need for NICE to reassess its criteria for the severity modifier.

This consulting report ‘Understanding societal preferences for priority by disease severity in England & Wales’ was commissioned and funded by The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI).

Understanding societal preferences for priority by disease severity in England & Wales