Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure

In becoming aware of the size and severity of the problems of mental illness it is easy to overlook the great strides forward which have been taken in the lifetime of many of us towards the goal which I believe we can and…

In becoming aware of the size and severity of the problems of mental illness it is easy to overlook the great strides forward which have been taken in the lifetime of many of us towards the goal which I believe we can and will reach. That goal will be reached on the day when we shall have won against mental illness a victory as splendid and as much to the credit of mankind as the victory we have now won over tuberculosis — that adversary which for so long seemed unconquerable.

I should like to draw attention to some of the great twentieth-century landmarks in the history of this crusade. In 1915 the Maudsley Hospital was opened in London. Its founder, Dr Henry Maudsley, had given the London County Council the sum of £30,000 on three very important conditions. The conditions were that it should deal exclusively with early and acute cases of mental illness—cases, that is, where there was most hope of effective treatment; that it should have an out-patient department where a man or woman suffering from mental illness could go for help without taking what then seemed the desperate step of actually entering a mental hospital as an in-patient; and that it should provide for teaching and research.

By this generous and far-sighted gesture, Dr Maudsley outlined what was to become the plan of campaign of his many successors who have fought for the same principles: to treat the mentally ill rather than simply to keep them in custodial care; to avoid segregating them from the rest of the community; and to explore the possibilities of understanding the causes of mental illness, and ultimately, of curing—or, better still, of preventing—the conditions responsible for it.

It is significant, also, that especial parliamentary sanction was given to the new Maudsley Hospital to admit patients without certification. This sanction was subsequently extended to all mental hospitals by the Mental Treatment Act of 1930—another honourable landmark in our history. For the first time, psychiatric hospital treatment could be sought voluntarily, and in good time, by those who were mentally ill Mental hospitals came slowly to be regarded as hospitals like any others, and not as places of confinement and despair.

It is during the last thirty years, however, that the most heartening advances have taken place. They are described in detail in this publication, so I will mention them only briefly.

There have been, for instance, the great discoveries of physical treatments, which, while not always curing, have mercifully alleviated the suffering of thousands of people. I am thinking especially of electro convulsive therapy, and of the newly discovered tranquillising and antidepressant drugs which have enabled us to control the extremes of irrational behaviour leading to violence or complete incapacity-and have thus made it possible for psychiatric patients to be treated without the humiliations and affront to human dignity involved in physical methods of restraint. Leg locks and strait-jackets are now looked on as savage emergency measures of the past and no longer shame the mental hospitals of our time. Even locked doors are widely looked on as relics of a past age.

These medical discoveries have led to a rapid rise in the number of admissions to mental hospitals of people who know now that they can look Mental Health Research Fund raises by public generosity some £30,000 a year-but this represents only one-tenth of what is given for cancer research.

The pharmaceutical firms allocate a creditable proportion of their revenue to research. But, whatever the total amount that is being spent, it is plainly nowhere near enough.

To my mind it is not a matter of what we can afford to spend on medical —and social-research in to psychiatric disorders. It is a matter of what we can afford not to spend. This booklet describes the costs of today in terms of human suffering but it is not only these costs of today which could be reduced. The benefits of any research we undertake now will, of necessity, be long-term benefits. The consequences of our failure to make such long-term investments will be tragedies for some of our children and grandchildren. It has been calculated that one among every nine girls aged six now will enter a mental hospital at some time of her life; and so will one among every fourteen six-year-old boys. We have it in our power to prove these horrifying calculations wrong.

We are, I feel sure, on the right lines at last. Mental illness is now a matter not for resignation or despair but is a field in which one can feel hope. However, as the late Lord Feversham-my greatly revered predecessor as Chairman of the National Association for Mental Health—once said, Government legislation cannot secure ‘the full benefits which Parliament intended for the mentally disordered unless the man-in-the-street plays his part in bringing about a new, hopeful era of development and understanding for the sick in mind.’

If we, as a people, insist that mental illness must be wiped out, and if we are resolved, every one of us, to play our part in whatever way we can, we shall not be defeated.

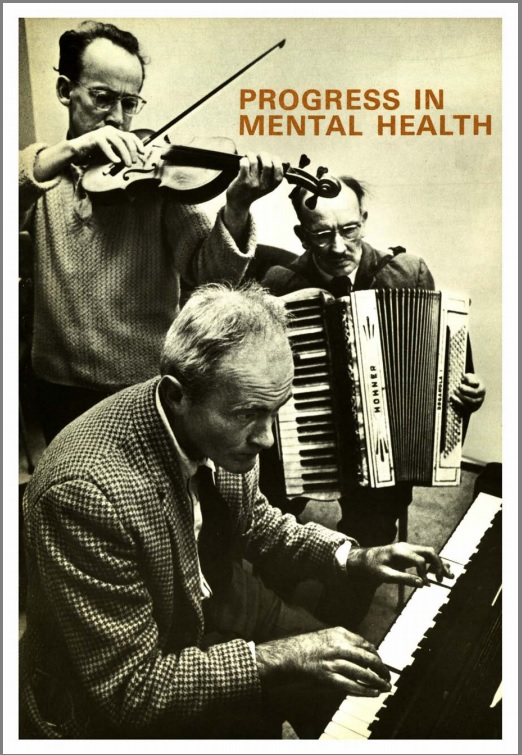

Progress in Mental Health